“A huge reason for why Korea’s modern music industry operates the way that it does, is because it developed during the age of television. While most other music industries developed during the era of the phonograph and radio, Korean popular music came about at a time in which TV was the primary medium through which people learned information and were entertained.” Hannah Waitt, K-pop journalist, in her history of K-pop series

Psy’s Gangnam Style was the first K-pop song I paid attention to, as I imagine it was for many of you, back in 2012. Prior to becoming a fan of BTS, I had a broad strokes understanding of the industry from the brief surge in Western media coverage around Psy’s breakthrough and a few sensational and heartbreaking industry scandals in recent years, but I was otherwise quite unfamiliar with any groups or their songs until this year.

While it’s not necessary to be well-versed in K-pop to enjoy BTS (in fact, they are oftentimes the very first K-pop act that a member of ARMY becomes a fan of), it is useful to have a grounding in the history and development of K-pop as an industry to understand just how extraordinary BTS's rise has been, because I’ve learned that BTS at inception was definitely not your typical K-pop group. This nuance is oftentimes lost in Western media coverage of BTS who follow this seductively simple train of thought: BTS are Korean men who sing in Korean and release popular music, ergo they must be K-pop! BTS's rise and extraordinary success has also meant that they have become the latest writers of the K-pop playbook, and are evolving the industry in new directions.

The genre known as K-pop outside of Korea can actually more accurately be characterized as a specific entertainment business model, with a strong export-oriented focus, for a genre of music that Koreans know within the country as “idol music.”

There’s a specific formula to the K-pop sound: “K-pop is an East-West mash-up. The performers are mostly Korean, and their mesmerizing synchronized dance moves, accompanied by a complex telegraphy of winks and hand gestures, have an Asian flavor, but the music sounds Western: hip-hop verses, Euro-pop choruses, rapping, and dubstep breaks.”

K-pop as an industry has been focused on conquering overseas markets practically since inception in the late 90s and has developed a number of tactics to increase a group’s appeal in foreign markets. This strong export focus is due to both the small size of the South Korean population (51 million in 2019) and how little profit music sales generate within the country. As Ju Oak Kim, an assistant professor at Texas A&M International University who researches Korean pop culture and media, told Vox: ““Selling the same exact song or exact same album, Korean acts could earn more than eight times more profit outside of Korea than inside.”

K-pop is part of the hallyu movement (“Korean Wave”) of cultural exports that first targeted Asian countries (Japan and China initially then Southeast Asia) with high-quality television series and movies in the late 90s, and has since become a global movement encompassing beauty, cuisine and video games.

To sell globally, most companies are eager to develop idols who have the language skills (unsurprisingly, English and Chinese are most coveted) and international background to draw global audiences. For example, the boy band EXO which debuted in 2012, had two sub-groups that performed and released music separately in different languages: EXO-K in Korean and EXO-M in Mandarin. BLACKPINK, the girl group who currently holds the mantle as the most popular K-pop group in the world after BTS, is composed of four members, three of which speak English fluently (Jennie, Rosé, Lisa) and two who were born abroad (Rosé in New Zealand, Lisa in Thailand).

No one expected BTS to make it big in the K-pop industry domestically, let alone internationally. As a Korean music critic and blogger note, “BTS employed none of these localization tactics. The group has no non-Korean member, nor does it have any song sung entirely in English.”

The only international market besides America that BTS has explicitly catered to has been the Japanese market as they have and continue to release entire albums in Japanese. If you’re not in the music business, you might wonder why they do this: Japan is the 2nd largest music market in the world after the US, primarily due to strict copyright laws and sustained support of physical album purchases. The effort is paying off, as their latest Japanese album, Map of the Soul 7: The Journey, sold over 500,000 albums in Japan alone in its first week.

China’s a bit of a conundrum for the K-pop industry as they are oftentimes caught between the escalating political tensions of the South Korean and Chinese governments. BTS and other K-pop idol groups are enormously popular in China, yet they have not been able to officially promote their albums or put on performances there in several years. With digital tools at their disposal, Chinese fans are still very much in touch with their idols and thus K-pop idols are still earning in the China market through lucrative commercial endorsements.

The Agency Model

“In the music business in the U.S., the artist is at the centre, and around that artist are different people providing services—including managers overseeing the business side, label executives releasing recording music, lawyers providing legal advice, agents managing tours, producers putting together a creative team, and stylists helping with fashion and beauty. Here in Korea, one company provides all these services to an artist. This 360-degrees approach is a unique feature of K-pop. We manage every aspect that has to do with the artist. We have a record label, we oversee concerts and other content, we have a management organization, we offer administrative structures… here, it’s all under one roof.” Bang Si-hyuk and Lenzo Yoon, co-CEOs of Big Hit Entertainment, quoted in Big Hit Entertainment and Blockbuster Band BTS: K-Pop Goes Global

In the late 90s, three entertainment agencies who would become synonymous as the Big Three of the K-pop industry emerged: SM Entertainment (SM Town), JYP Entertainment, and YG Entertainment. As John Seabrook, author of The Song Machine (a must-read if you’re interested in the behind-the-scenes of the global pop music industry), explained,

“These agencies act as manager, agent, and promoter, controlling every aspect of an idol’s career: record sales, concerts, publishing, endorsements, and TV appearances.”

Idol groups are literally the product that these agencies produce. They audition thousands of youngsters a year, some barely in their teens, around the world and put them through a rigorous trainee program to mould them into idols worthy of that title: singers and rappers “worshipped by their fans, who admired them not just for their vocal and dance talent, but also for their seemingly god-like images of perfection.”

In addition to singing and dancing, there is a lot of focus on behaving like an idol and trainees are schooled in “facial expressions, public behaviour, attitude, and personality development.” Lee Soo Man, the founder of SM Entertainment, is widely acknowledged as the architect of the modern idol training system after his first act, Hyun Jinyoung, failed after being arrested on drug charges.

As streaming began to decimate music sales in the late 2000s, the need for ever more diversified revenue streams and promotional opportunities meant that the trainee system expanded to include acting lessons and modelling to take advantage of K-dramas’ global popularity and the importance of commercial endorsements.

It’s an intense gauntlet of training that many young hopefuls endure for the dream of debuting one day as part of an idol group. They’re daunting odds: on average, only one in ten will make it.

Idols as Product & Service

“I think that idols are closer to the service industry. There is a clear target audience, and there is a preference that this target wants. So I think an idol has to fulfill the virtues this target audience wants. When that is satisfied, consumption occurs. Any singer will do a basic amount of fan service, but for idols that’s much more important.” Bang Si-Hyuk, founder of Big Hit Entertainment, in a 2013 interview (translation)

Many Western music critics dismiss K-pop as overly manufactured because the agency model means that the idol is often reduced to the role of performer with the “beautiful face and an irresistible body to endorse the music and choreography that has already been pre-determined for them.”

But what’s forgotten in that assessment is that music is only one aspect of the K-pop “product.” Music sales are typically not the biggest revenue drivers of entertainment companies. Instead, concerts, paid appearances, endorsements, merchandising and licensing deals make up the majority of revenue and these are activities that become much more lucrative when idols can make fans feel like they’re friends with them.

“Fan service” is the term used in K-pop to categorize the whole gamut of activities that idols do to make fans feel like they’re dating or friends. Much of it is done virtually through digital platforms like fan cafes and behind-the-scenes social media content. It’s also why it’s so important for K-pop idols to spend so much time promoting themselves and their personalities on Korean variety shows. BTS has grown enough in success that they have been able to step off the typical K-pop variety show promotional circuit (although they do film their own in Korea and release more behind-the-scenes content than any idol group), but not before they filmed this very illustrative and typical fan service video of them being the objects of desire at a fictional BTS high school:

The offline component of fan service happens at fan meetings. Idols greet their fans one by one, and spend some time interacting with them, whether that’s through a handshake or hug, or even letting them touch their face.

It’s pretty understandable why most agencies have an explicit ban of dating in idol contracts: to preserve the illusion of the idol as a fantasy romantic partner for as long as possible. While Big Hit is known for not writing in behavioural bans in their contracts like dating, rest assured that if the company has any say in the matter, fans will not find out about a member’s partner until they’re at the altar.

Is K-pop a musical genre?

“I think [K-pop’s appeal lies in]... how cool and showy performances come together with trendy music to be an experience for the sight and hearing. I don’t think that language is an emotional barrier for music anymore, wherever you are in the world. Because the idea of ‘visual music’ is becoming stronger, and K-pop especially brings together performance and music, I think there is enormous potential for it to compete well with other styles in the worldwide music market.” Pdogg (Kang Hyo Won), Big Hit Entertainment and BTS producer, in a 2017 interview (translation)

K-pop, with its emphasis on the “total package” of performance, gives audiences many entry points into enjoying the music that don’t involve understanding what the performers are singing. Idols are consistently honing their performance skills as the most important promotional channel for K-pop idols is Korea’s ubiquitous weekly televised music programs. As Vox explains, “a K-pop group’s success is directly tied to its live TV performances.” For context, there are six main weekly music shows in Korea that fall on each day of the week except for Monday:

- Tuesday: SBS MTV’s The Show

- Wednesday: MBC Music’s Show Champion

- Thursday: Mnet’s M! Countdown

- Friday: KBS’s Music Bank

- Saturday: MBC’s Show! Music Core

- Sunday: SBS’s Inkigayo

For American audiences, the closest equivalent I can conjure up for these Korean music shows is a mashup of the performances from The Voice or American Idol and MTV’s Total Request Live with the concert stage feel of the former and the countdown format of the latter, but imagine that your favourite artists are on one of these shows almost every day of the week when they’re in peak promotion mode. Performances on morning (Good Morning America), daytime (Ellen), or late night shows (Colbert, SNL) in America are at a much smaller scale as they usually don’t have a dedicated concert stage and the specialized production know-how for musical performances that these Korean music shows excel at. A great way to see this for yourself is to compare BTS's comeback stage performance of “Black Swan” on the Korean music show M Countdown with a performance of the same song on James Corden.

The M Countdown performance features an elaborate set and a plethora of camera angles that the producers weave together seamlessly to highlight key elements. In comparison, the Corden performance feels literally constrained - by the small size of the stage and the paucity of camera angles available.

One bright light amidst the pandemic for fans has been the pride they have felt in BTS's ability to showcase themselves to the fullest extent of their creative and artistic potential in front of the all-important American audience because they are filming everything on "home turf" in Korea. Without the usual constraints of American platform stages, BTS and Big Hit have been able to leverage Korean creative production know-how to create some of their grandest televised moments yet.

Jimmy Fallon hosted #BTSWeek in late September where the group debuted a new performance every night. To continue the "Black Swan" comparison, enjoy BTS's performance of "Black Swan" on its most impressive stage yet.

It’s a huge milestone for idols to receive their first number one ranking on one of these shows, and BTS got their first win for “I Need U” on May 5, 2015, nearly two years after debut, on SBS MTV’s The Show.

These music shows each have a complicated ranking system that fans attempt to game to help their favourites. It also cultivates a highly engaged sense of fandom that has now become global thanks to ARMY and other global K-pop fanbases. As Billboard explains, “This brand of highly coordinated fan efforts might have been new territory for Western fandom, but it’s the norm for K-pop fans who watch music shows. “Fans have passion and they want their idols to win,” says [Paul] Han [co-owner of the English-language K-pop blog allkpop] over email. “Album sales, digital sales, streaming all help in the point system of Korean music shows so that only drives consumerism even further. You see some fans doing bulk-buying -- buying hundreds of albums -- just so it will help their idols secure a win.”

This performance culture has a direct impact on music production. Vox: “Because of this dependence on live performance shows, a song’s performance elements — how easy it is to sing live, how easy it is for an audience to pick up and sing along with, the impact of its choreography, its costuming — are all crucial to its success.”

Given the performance imperative - let’s try to pin down a more elusive question: is K-pop a musical genre?

Their leader, RM, described K-pop as such in an interview: “When I get questions about why is K-pop is so popular; I always tell them K-pop is like a great mix of music, videos, visuals, choreography, social media and real-life contents.”

As BTS has evolved, they have helped to redefine global popular music while remaining rooted in K-pop. I would argue that with BTS, we’ve broken into new territory with a musical act that has developed during the age of social media and mastered it. BTS has sold the most number of albums in the US at the midpoint of 2020 according to Nielsen, yet the average person on the street, especially someone who is not, as they say, “very online,” may have never heard of them or their music.

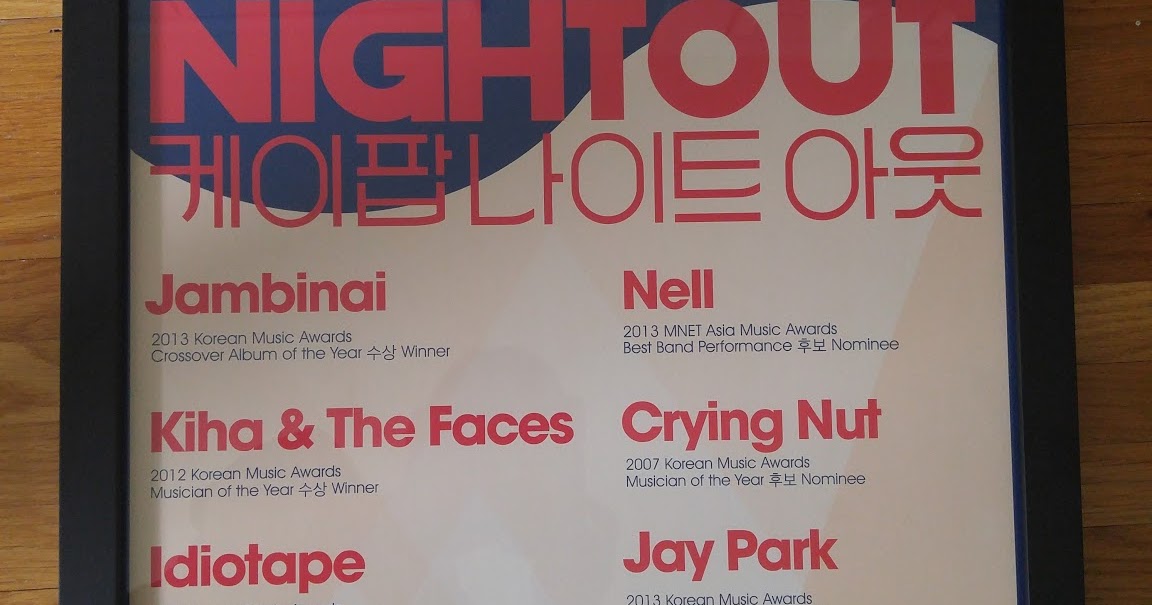

Learn more about K-pop